This personal essay was originally published in Creeper Magazine Issue 1.

I don’t remember the first model kit I built.

I remember the small metal tins of Humbrol enamel paint. I remember levering the lids off with a flathead screwdriver, and struggling to fit them back into place when paint clung thick to the edges of the metal. I remember the X-Acto knife I would use to cut kit pieces from their plastic frames (years later I would use this same knife to cut myself in search of answers to my teenage angst), I remember the chemical smell of the paint and the glue, and the sticky consistency of the white paint compared to any other colour.

I don’t remember building the 1:72 scale model of the SR-71 Blackbird spy plane, but I must have been proud of it, because I remember showing it to my dad. I remember him joking that Saddam Hussein was sitting in his office, building the same models. I assume the joke was at Iraq’s expense—the country too backward to gather intelligence in any traditional way, relying instead on a child’s toy to know what it was that they faced in an adversary like America. The joke surely wasn’t at the expense of America’s arrogance in attempting to police the entire world, or the cultural saturation of this idea of righteous American war against, first, Communism, then Middle Eastern dictators, and later (and still), the vaguer notion of “terrorism”.

(Christmas 1989, and I receive my first GI Joe figures and vehicles. I had seen my father buy these toys at Kmart, but had believed him when he said they were for a cousin, rather than myself. I would become obsessed with GI Joe, but it all began because I asked for a My Little Pony. I can only assume my father feared I’d grow up gay if I were to receive a bright purple horse, so instead it was GI Joe. But this is a story about model kits, not action figures. Though they are both stories of the cultural acceptance of war.)

I don’t remember if I laughed at dad’s joke, but I remember thinking I understood it. Saddam Hussein was the villain from the television. He deserved ridicule. He deserved it in the form of jokes from middle-class white men all across the Western world. He deserved it in the form of racist cartoons in major newspapers.

My father didn’t serve in Vietnam, but his father served as a gunner and radio operator in a Beaufort bomber in the Pacific theatre during World War II. His father’s father served in the Scottish army during World War I—one of the many who returned from the war and would not, or could not, speak of it, a man broken by what he’d seen and/or done. I don’t know if this weighed on my father, if he felt that he was somehow breaking the line of White warriors. But when the television tells us that we’re at war with Communism, then isn’t consumerism a sort of combat? Isn’t each swipe of the credit card the same as pulling the trigger?

(The CIA backed The Baath party in Iraq—which counted Saddam Hussein among its numbers—in a coup against the Communist-aligned General Qassim. At this stage it should be a given: Of course America would have been instrumental in bringing its future enemy to power. How many times has America built its own bogeymen from pre-existing kits they barely understood, gluing the pieces together with American money and American weaponry? How many more times can they manage it before their empire crumbles?)

My dad might not have first-hand experience of war, but he was a veteran of Capitalism’s trenches. My parents had lost their business and our family home in the “Recession we had to have”. Still, he could not lose faith, the lifelong salesman a zealous soldier in Capitalism’s army even now. By the time I was building my SR-71 Blackbird model, Communism had been defeated. (I remember where I was when the Berlin Wall came down: playing with GI Joes on the floor of a family friend’s living room. But that is still a different story.) No longer would the armies (or operatives) of America and its allies be dispatched to far-flung corners of the globe to take a stand against an ideology. But the hunger for war remained.

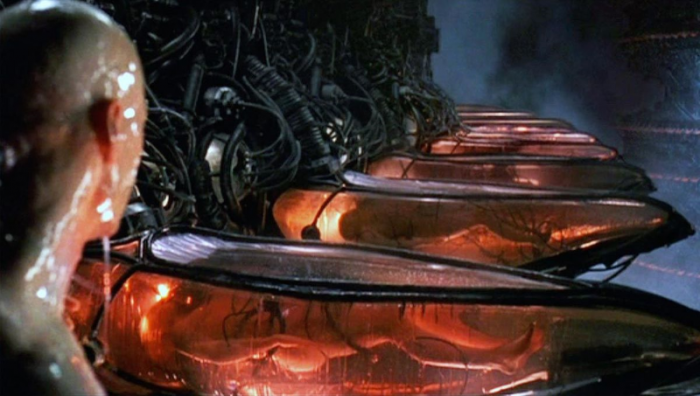

The first Gulf War is contained within a reticle—a rectangular crosshair laid over grainy aerial footage. If reporters on the ground in Vietnam helped turn public consciousness against that War, video footage direct from the nose of state-of-the-art missiles had the opposite effect. How could America ever lose another war with this kind of technology? (The same way they lost Vietnam. The same way they’ll lose the War on Terror.)

Propaganda in its purest form. No rhetoric, no words, just pixelated images, just explosions flaring green and black in night-vision. It was a war fought via CNN as much as any traditional weapon. The war was a demonstration for all the world—for America’s enemies and its allies—that not only could they target you with pin-point accuracy, they could watch the missile hit you in real-time. It made explicit the relationship between missile and target, connecting them via the thread of video, the missile’s visual feed and the target’s life ending in the exact same moment, a life reduced to static on a TV screen.

(It was the precursor to drone strike footage, with the added bonus that the speed of a missile’s journey meant civilian viewers would never see the targeted weddings, the dead journalists, the dying children.)

If aerial and missile footage is the Gulf War image that looms largest in our collective memory, it’s only because the rest of it has become normalised by the endless acceleration of late capitalism. But there are countless other artifacts of this war, gathered beneath the consumerist banner. Flashy newscast graphics like something you would see in Paul Verhoeven’s Starship Troopers a few years later, unashamedly bringing the war into living rooms with an air of excitement. Desert Storm trading cards, released by Topps and other companies, sadly missing the bubble gum that would come with your NBA, NFL, or TMNT cards (the smell of the gum lingering on the cards years after the gum itself was chewed into a tough, flavourless pink blob).

That there have been Gulf War video games should surprise no one, but the variety of titles that were released during or soon after the war is demonstrative of the saturation of the conflict in popular culture. 1991 saw the Macintosh game Operation Desert Storm, released by Bungie (yes, that Bungie), the coin-op Desert Assault, and a Gulf War mission disk for the flight simulator F-15 Strike Eagle II. In 1992 we saw Desert Strike: Return to the Gulf, Operation Secret Storm (starring a secret agent named George B), and Super Battletank: War in the Gulf. In the years since, many other games have been released, all commemorating America’s swift, vicious victory.

(Do not forget the children of Iraq and Kuwait—children of globalisation as much as any of us in the West—who lived through the war, experienced first-hand the sound and fury of military might, then had the war sold back to them in video game form. This disconnect is precisely what Fatima Al Qadiri captured in her Desert Strike EP: the experience of sitting on her rooftop, watching green lasers and anti-aircraft fire streak through the wide black sky, living through the invasion and then liberation of Kuwait, and returning to the war again a year later with the video game Desert Strike. “Playing that game really screwed with me, it really messed me up in the head, because I was just like ‘how does this exist in a format that I can play?’ I couldn’t even describe how disturbing the feeling was. […] It’s really cruel and disgusting when video games are made out of real war. It’s just a disturbing thing, and anybody who’s survived any war conflict and played a video game about it afterwards can tell you how disturbing that is. It’s making something really profound and deep and disturbing into something trivial and fake.” [Source])

And then there were the model kits.

The best war propaganda is that which you don’t have to force onto people—they eagerly buy it from you in myriad forms.

I remember the AH-64A Apache, the AH-F1 Cobra, the UH-1 Iroquois, and the UH-60A Black Hawk helicopters. I remember the jets and bombers, the F-4 Phantom, the F-15 Eagle, the F-16 Fighting Falcon, the AV-8B Harrier II, the F-14A Tomcat, and the F117-Nighthawk. I remember the names like I remember the names of my childhood friends. I remember sitting at my small desk, carefully painting these miniature war machines in camouflage patterns, or the flat grey of naval jets, or the matte black of stealth bombers. I remember the missiles, the sticky white paint I would use for their bodies, and the small flourishes of colour on their tips and their fins. I remember gluing the model pieces together, the superglue tacky on the skin between my fingers. I remember tying lengths of fishing line around the helicopters and planes so they could hang in the air above my bed.

Were these models—like the Gulf War video games—also for sale in Iraq and Kuwait? The same vehicles that filled the skies overhead also filling the shelves of stores, each one a brute force injection of plastic and ideology, each one a talisman of American superiority. How many Kuwaiti and Iraqi children would—like me—while away an afternoon building model kits? Cutting model pieces from their frames, carefully painting each model to match the ones dropping bombs on their countries. Would they have wanted these war machines to hang from the ceiling of their bedrooms? Would they have wanted these war machines to hang in their air above their heads?

When your toys are weapons of war, does war itself become a game? Do bombings on the nightly news become like explosions in an action movie? (Imagine that disconnect. For Russians, for North Koreans, for Chinese, for Iraqis, for Nigerians, and all the other people demonised by Hollywood. To have yourself-as-villain on the silver screen, as large as god and twice as loud.)

I remember the Sopwith Camel model kit I never built. It was larger than my other models, made in a different scale. I can’t remember if I never built it because it was given to me just as my interest in model building had begun to wane, or if I never built it because it was too disconnected from modern life. The World War I biplane wasn’t made with stealth technology. It couldn’t drop a nuclear bomb. It wasn’t on the nightly news, or on trading cards. It wasn’t in combat in the skies over the Middle East. People weren’t dying in Sopwith Camel bombardments.

My bedroom ceiling was a microcosm. Jet fighters, bombers, and attack i hanging from lengths of fishing line that I could imagine were invisible. In macro, they hung in the air over Kuwait and Iraq, destroying military targets and killing civilians. This is why I was so enamoured. They were real. They were deadly. They were righteous.

My parents bought the model kits for me, but I bought the war.