I swear I’m not actively trying to talk about my upcoming book with every post, but seeing as it is my first book, this whole experience is one of many firsts. So today I want to talk about editorial, and why it might be tough, but very, very necessary.

Like I said, this is my first book, so I’m going to assume (perhaps wrongly?) that my experience is more-or-less the norm, and tell you about how it has all been unfolding for me, so if/when you find yourself in the same position, you know what to expect.

Step 1: Editorial Letter

Now, I’m not sure why it’s called an ‘Editorial Letter’, or even if that’s an industry-wide term, but it is far less formal than it sounds. It’s basically just addresses issues in your manuscript in a loose, big-picture kind of way. This is where your editor says “Your book is great, but this, this, and that don’t quite work as well as the rest.”

Chances are, the things that your editor points out are likely things that you weren’t 100% sure on yourself, but after beating your head against the keyboard on a number of rewrites, you simply couldn’t come up with a better way to to do it. But guess what? Now you have an editor on your side, and they’ve already agreed to publish your book, so if they want it to be the best book it can be when it comes to market, they HAVE TO HELP YOU FIX IT.

This editor is likely working with you because something in your manuscript spoke to them, because they love it, because they believe in it, or some combination of those things. They also have likely edited (or at least read in slush) any number of manuscripts, so you can trust that they’re going to have a fine eye for picking out issues in your manuscript. They may also be accomplished writers themselves. Either way, trust that they know what they’re talking about.

When it comes to fixes, they might have ideas that completely resonate, and which you can immediately see and grasp, and which set your mind spinning with all the ways you’re going to incorporate these changes, or they might have ideas that don’t sit quite right with you. But, hey, this is a dialogue, so if it’s the latter, talk about it. Try and figure out why they’ve made those suggestions so you can come up with your own solutions that answer the same questions.

(Or, in other words, don’t be stubborn, don’t be a dick [obviously], don’t try and argue with them when they want to kill your darlings [they need to die for a reason], and realise that just because they want to publish your manuscript it doesn’t mean that it’s perfect.)

Anyway, after you’ve fixed those bigger-picture issues and you’re both happy with the changes, it’s time to move on to…

Step 2: Line-Edits

For some reason, this step caused my anxiety to peak. Personally, feedback from friends is easy, no matter how thoroughly it tears my work apart, because I know them, I understand their tone and exactly where they’re coming from. When it comes to people I know less-well however – like an editor I’ve only met in person a couple of times, or absolute strangers on a critiquing website – the criticisms get right under my skin for some reason.

I realise this is just down to me and my mind-spiders, so perhaps none of this is relevant for you, Miss No-Mental-Illness-For-Me, but hey, I’m talking about my experience. It’s not that my (brilliant) editor (Carl Engle-Laird) was harsh or anything like that – again, this was totally about me, not the experience – but going through the line edits was almost paralysing. I’d be able to spend two (distracted, anxious) hours at it, and then need to stop. By day three I’d convinced myself that the manuscript was so shit the only reason they decided to publish it was because it was somehow the least shit out of the submissions they received and they’d taken pity on me. Needless to say, that was a dark day. Thankfully, by day five, nearing the end of the manuscript, I’d completely turned a corner on the line-edit process. I’d come out the other side and realised all the things that would have been obvious if it weren’t for the anxiety:

- It’s a good manuscript.

- It’s not shit.

- The line-edits were to make it sing, not to tell me that I’m a bad writer and I should feel bad.

- The process had made the manuscript that much better.

Seriously, I was so happy with the manuscript at the end of that first run-through that I was slightly embarrassed that an earlier draft had gone out to other authors in the hopes of getting blurbed. The word I’ve been using to describe the effect of the edits is ‘elevated’ – it pointed inconsistencies (or things that weren’t necessarily inconsistent, but which needed clarity), and completely elevated the prose of the book by pointing out over-used verb forms and sentence styles, repeated words and phrases, and probably other things I’m forgetting.

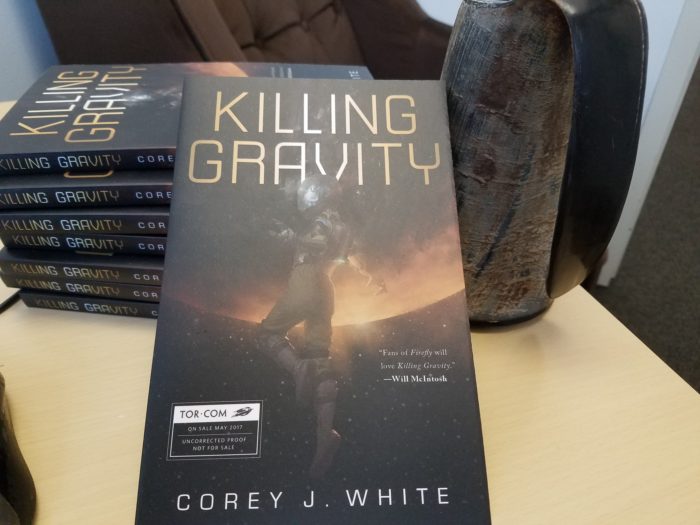

I realise that when it comes out, Killing Gravity is still not going to be everyone’s cup of tea, but I’m not satisfied that it is a damn fine cup all the same.

You’ll go back and forth a couple of times with the colours of Track Changes scarring your manuscript until you’re done. Up next is…

Step 3: Copy-Editing

Which is the step I’m waiting on now, so I can’t actually tell you much about it. Though I’m assuming it will be someone with extremely technical knowledge of the English language telling me all the things I did wrong and telling me that all my dumb, made-up sci-fi words are entirely too-dumb to see print. But hey, we’ll see, and if the process is interesting enough, maybe I’ll write about that too.