This piece was originally published as a bonus issue of the Nothing Here newsletter.

Simulating even a single posthuman civilization might be prohibitively expensive. If so, then we should expect our simulation to be terminated when we are about to become posthuman.

For a while I kept hearing that physicists or philosophers – or some other type of expert that starts with ph – were certain that we were living in a simulation, and for a time I kind of accepted that. These people are smarter than me, I thought, so they should know. What I didn’t realise was that so much of this belief in simulation theory was exactly that – belief. Faith isn’t just for Christians and Bitcoin evangelists, and it’s becoming more and more apparent just how strong a grip it has on Silicon Valley and the cult of Kurzweil’s singularity.

I assume there have been many books written on the topic of simulation theory, and indeed – as pointed out in this episode of Philosophize This! (libsyn, youtube) – it can be seen as a very cybernetic take on Descartes Evil Demon, however, my understanding of simulation theory is coming from this paper by Nick Bostrom. The paper is dense, but it’s short, and well worth the time required to read it. There is a lot of interesting detail to it, but I’ll attempt to break it down as simply as I’m able.

Basically, Bostrom lays out three options, one of which must be true. (1) Humanity will go extinct before reaching a post-human state. (2) Humanity will reach a post-human state, but for some reason there will be a consensus that simulating realities isn’t something to be done (perhaps they’ve all read Ligotti’s The Conspiracy Against the Human Race and agree that creating life means creating suffering. Or maybe it’s just gauche, like a gold toilet. Or maybe they are so unlike us that they would simply see no appeal in running an ancestor simulation). Or (3) We’re living in a simulation.

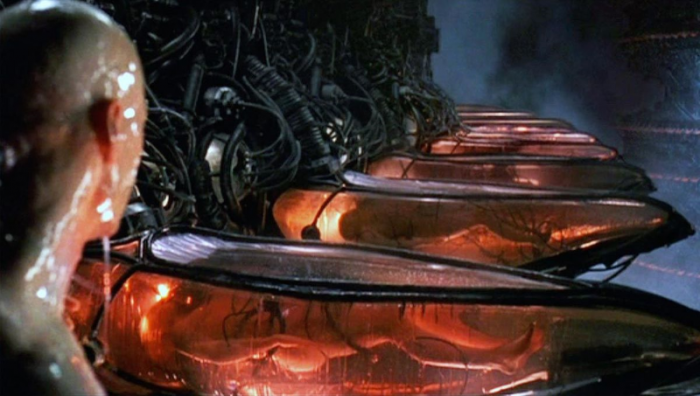

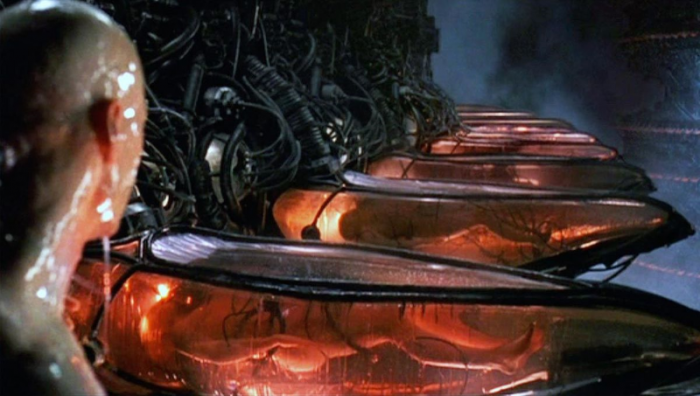

Now, at first glance, (3) might seem like a pretty extreme conclusion-jump, but a good chunk of the paper is laying out why this would be the case. In short, it’s based on extrapolations of the computing power available to post-human civilisations that would be able to manipulate matter on a massive scale, creating planet-sized computers and the like, versus that amount of “computing power” used by the human brain to process the world around us. Basically, the amount of computing power available to post-humans would make simulating a reality like ours simple to the point of it being child’s play (perhaps literally – we could be living inside some post-human child’s Tamagotchi). Now, if it’s that simple to simulate a reality like ours, and computing power is so readily available to post-humans, then if they do make one simulation, they could make billions, or even trillions of simulations. And if the civilisations within those simulated realities reach a post-human state, then they themselves might create simulated realities within their simulated reality, meaning there could potentially be a near-infinite number of recursive simulated realities built upon the base of the one prime reality.

I said before that the widespread acceptance of the simulation theory comes down to faith – well, here is the second pillar: statistics. And we all know there are three kinds of lies: lies, damned lies, and statistics.

Now, I’ve got no problem with Bostrom’s paper – the arguments are interesting and well-made. He even suggests that one should weight options 1, 2, and 3 evenly – but it’s still the statistical basis laid out in his paper that provides the “hard numbers” to the faith of all these wannabe post-humans; the foundation they’re using to build this house of hope and assumption.

If you assume/hope/have faith that one day we will be able to simulate reality, then you must believe that we are currently living within a simulation. Because out of the trillions of possible simulations outlined above, there can be only one base layer of reality – and what is statistically more likely, that we are one of the (relatively) few people living in the base reality that one day theoretically spawns all the simulated realities, or that we’re part of the exponentially larger group of simulated beings?

Even with statistics on the table, it’s still the assumption that irks me more. This belief in Silicon Valley’s constant, inexorable progress (as though the whole place hasn’t been co-opted by the military industrial complex and the whims of VC finance), that of course they would be able to simulate an entire universe if only they had enough computing power and funds, and did away with unnecessary regulation…

They have completely bought into the Californian Ideology and its odd mix of libertarianism, right-wing conservatism, and liberal values. It’s the idea that technology will set us free, but only the “us” that is privileged enough to live in areas with some of the highest cost of living, and devote all of their time, energy, and focus to the goals of their newest start-up. It is an ideology of exceptionalism, and of course those deemed exceptional are white men – those who have been given all the tools and opportunities to be “resourceful entrepeneurs”:

[…] each member of the ‘virtual class’ is promised the opportunity to become a successful hi-tech entrepreneur. Information technologies, so the argument goes, empower the individual, enhance personal freedom, and radically reduce the power of the nation-state. Existing social, political and legal power structures will wither away to be replaced by unfettered interactions between autonomous individuals and their software. These restyled McLuhanites vigorously argue that big government should stay off the backs of resourceful entrepreneurs who are the only people cool and courageous enough to take risks. Indeed, attempts to interfere with the emergent properties of technological and economic forces, particularly by the government, merely rebound on those who are foolish enough to defy the primary laws of nature. The free market is the sole mechanism capable of building the future and ensuring a full flowering of individual liberty within the electronic circuits of Jeffersonian cyberspace. As in Heinlein’s and Asimov’s sci-fi novels, the path forwards to the future seems to lead backwards to the past.

Ultimately it is regressive and traditionalist, even as it claims to be the ideology of futurity and progress. It is no wonder then that we have stalled out, both technologically and culturally (in the mainstream, the fringes of culture are as exciting as ever), never reaching the level of technological progress promised to us by the science-fiction of the mid-to-late 20th Century. That truly innovative drive has been co-opted by Capital.

Recalling the clumsy special effects typical of fifties sci-fi films, I kept thinking how impressed a fifties audience would have been if they’d known what we could do by now—only to realize, “Actually, no. They wouldn’t be impressed at all, would they? They thought we’d be doing this kind of thing by now. Not just figuring out more sophisticated ways to simulate it.”

That last word—simulate—is key. The technologies that have advanced since the seventies are mainly either medical technologies or information technologies—largely, technologies of simulation. They are technologies of what Jean Baudrillard and Umberto Eco called the “hyper-real,” the ability to make imitations that are more realistic than originals. The postmodern sensibility, the feeling that we had somehow broken into an unprecedented new historical period in which we understood that there is nothing new; that grand historical narratives of progress and liberation were meaningless; that everything now was simulation, ironic repetition, fragmentation, and pastiche—all this makes sense in a technological environment in which the only breakthroughs were those that made it easier to create, transfer, and rearrange virtual projections of things that either already existed, or, we came to realize, never would. Surely, if we were vacationing in geodesic domes on Mars or toting about pocket-size nuclear fusion plants or telekinetic mind-reading devices no one would ever have been talking like this. The postmodern moment was a desperate way to take what could otherwise only be felt as a bitter disappointment and to dress it up as something epochal, exciting, and new.

–David Graeber

Back to Bostrom… If you believe in the ability of humanity to become post-human and (/or) create an entirely realistic simulated universe, then we must be living in a simulation. It’s almost tempting to believe, isn’t it, with the seeming utter chaos of recent years? And it’s a belief that could gain wider traction – especially as there is already an online contingent espousing the gospel of the Large Hadron Collider. This is the belief/suggestion that the LHC accidentally destroyed our reality in 2012 and so we’ve been shunted over to an unstable or corrupted simulation (whether we were real or in a stable simulation prior to 2012 is unclear). We long for simple answers, for order amongst the chaos, even if that ‘simple’ answer is one that calls into question the nature of our reality itself.

[There’s a tangent here about predetermination. I read an Alan Moore interview at some point last year in which he laid out his belief that we’re all living entirely pre-defined lives, that free will is a myth. I think that must be easy to believe when you’re respected as one of the greatest writers of recent times, but personally it made me angry. I think it was a shadow of the rage I once had for God, before I was mostly able to scrub the Christian meme from my mind. If someone else (or some great plan) had already set me on this path and I was powerless to alter it, then what the fuck is the point? I considered writing something about predetermination versus free will, but all I had was anger – besides, people much smarter than I have already written tomes on the topic.

If everything is predetermined, then are we really alive, or are we simply characters in a movie that is playing on someone else’s screen? Is everything we do predetermined but able to be altered by someone else? Either a god figure (the ‘player’) or a ‘player character’ who’s inside the simulation with us?]

But the simulation theory doesn’t sit right with me – not because it means our lives are less meaningful (because even if it is a simulation, it’s real to us), and not because it would mean I didn’t have free will, but because of the hubristic wank constantly spewing out of the mouths of the tech bros who are so enamoured with the idea.

Last year I read N. Katherine Hayles’ How We Became Posthuman, which looks at cybernetics, focusing on the cybernetic conferences that ran from 1946-1953, other cybernetic theory and advancements of the 20th Century, and some relevant examples from science-fiction/pop-culture.

The focus on those cybernetic conferences can make large swathes of the book quite dry, but the literary touchstones Hayles uses include some of my favourite authors, like Burroughs and Dick, so on balance I found it enjoyable and enlightening.

In it, Hayles talks about one of those early cyberneticists who designed a system that mimicked the behaviour of a biological system. Being that this was a cyberneticist presenting this project to a clique of other cyberneticists, it was greeted with acclaim, but all I saw was the black box problem that is plaguing current instances of machine learning neural networks. In short: engineers rarely understand how a neural network comes to the conclusions it comes to. So, just because the cybernetic system outputs something analogous to a biological system, that doesn’t mean you have recreated said biological system – all you have done is created a cybernetic system that can output something analogous to a chosen biological system.

Without an understanding of what happens inside the biological system, how can you recreate it? How can you simulate it? Without an understanding of the many and varied complexities of plant life, fungal life (seriously, there are stunning discoveries about plants and fungi being made right now, particular the interconnectedness of plant systems), microbial life, quantum physics, or the human brain (we aren’t even entirely sure why people need sleep), then how are we meant to be able to simulate anything, let alone an entire reality?

Not to mention the fact that knowledge seems fractal, with each new discovery opening up new paths of exploration. Perhaps it is literally impossible to understand our universe well enough to simulate it.

[But this is interesting because what if we are living in a simulation? And what if knowledge appears to be fractal because the computer we’re all caught within only begins to simulate those areas of knowledge as we begin to discover them. What if the moon was only simulated at a higher resolution when we flew to it? What if we haven’t returned since because our operator has decided the computational cost of simulating the moon at high resolution is too much?

Simulation-evangelists might be taking everything on faith, but I’m staunchly opposed to it out of some sense of simulation-atheism. Which is correct? And does it matter?]

But I shouldn’t be surprised that simulation-believing tech bros care only about the output – the final result rather than the internal workings it took to get there. Silicon Valley has entirely succumbed to VC finance and has become a land of slick demos, high fidelity mock-ups, razor-honed design sensibility, and – let’s be honest – grifters. Funding doesn’t come from a detailed breakdown of a system’s internal workings, it comes from the hard sell, the presentation, the surface. Thaneros is, of course, the prime example here. The proposed technological breakthrough was scientifically impossible, but it didn’t stop them from collecting hundreds of millions of dollars of seed money.

We live in a mundane world (or simulation) forever waiting for the world that has been promised to us by PR and advertising.

Another area that’s relevant to this discussion is video games. If you want a precise encapsulation of both PR bullshit and simulation, go no further than Peter Molyneux. Molyneux made a name for himself as the head of Bullfrog, the company responsible for many classic games, including Syndicate, Theme Park, Dungeon Keeper, Populous, and others. They were systems-driven games – simulations, but of a lighter mode than the likes of SimCity.

While that looks like a pretty impressive CV, Molyneux’s real gift was bullshit. I can still remember the promises he made concerning the RPG Fable, convincing myself, many other gamers, and members of the gaming press that the game would feature reactivity and simulation of the sort not seen in RPGs ever before. It was claimed that the NPCs would have their own lives – that they would be fully simulated people, if you will – but in the end all this boiled down to was a set schedule the NPCs would follow. Just because the blacksmith left his house at 7am, walked to his workplace, and stood around repeating an anvil-beating animation for 8 hours before returning home, that doesn’t mean there was anything deep or interesting happening beneath the surface (or indeed, on the surface, as Fable turned out to be a fun but ultimately hollow experience). Like the cyberneticists before them, the developers thought (or at least claimed) that the output – a NPC going “to work” at a pre-defined schedule – was the same as simulating that NPC’s “real” life. But did that NPC have other concerns or a rich internal life? No. He was a digital shade that you could ignore or murder as you saw fit.

Interestingly, Bostrom’s paper also mentions individual simulations – where ‘you’ are the only real person being fully simulated and everyone else is an NPC. I say it’s interesting because it seems that this deluded solipsism is also becoming more common, to the point where it has become a meme. I worry about the implications if this gets more widespread – how easy will it be for someone to kill people who they only see as NPCs? Or without taking it to extremes – how difficult would it be to get someone to act toward the common good when they literally see everyone else as backdrop to their story?

But could your role in the simulation of your life be pre-determined, even if you were the only ‘player character’? And if so, how are you different from the NPCs?

It’s the central question, isn’t it: what does it really matter? If you’re in a simulation, you can’t break free of that simulation, despite what the Matrix told you. We are here. We are living in this universe, whatever form it holds, and all we can do is live our lives to the best of our abilities. Whether we do that for some god, some post-human child, or for ourselves, all that matters is that we live well. Or that we at least try.

ess

ess