I’m not convinced that Solarpunk will become the next true movement of SF (I feel like it could easily go the way of Steampunk, becoming more of an aesthetic movement rather than a literary one with sociopolitical importance, but I’ll get into the -punks at some other time [and remind me to tell you how I invented cli-fi years ago, but I called it Ecopunk {but never managed to finish my Ecopunk thriller}]), but this is some very interesting food for thought.

On The Political Dimensions of Solarpunk:

Novelist Bruce Sterling […] says that the future is about “old people in big cities afraid of the sky.” This is inexorable. Barring radical cataclysm, the reasonably inevitable trends of urbanization, an aging populace and climate change will set the stage for life in the coming five decades. If you are a human living in the middle of the 21st century, chances are you will be elderly — or surrounded by the elderly. Chances are you will live in a city. Chances are your community, country and supply chains will be plagued by some combination of extreme weather, rising sea levels and droughts.

These are the facts we must build on and around, whether we are making solarpunk fiction, solarpunk fashion, solarpunk infrastructure, or solarpunk political demands. If solarpunk is to back up its optimism with meaningful solutions, or even meaningful notions, we must consciously consider how to respond to each of these trends.

Read the whole thing, but I’ll warn you now, it’s a long one.

And the above points to this: Notes Towards a Manifesto, which is shorter and shallower, but still interesting, and a better bet if you’re short on time and/or processor cycles.

And if you do want to think about Solarpunk fashion, it’s probably worth reading the below excerpt, taken from Deb Chachra’s Metafoundry Newsletter, about textiles and fashion after our current fashion industry has become so much dust inside so many abandoned sweatshops:

At some point in the 90s, I got my hands on modern synthetic technical textiles for the first time, made of polyester fibres that were now fine enough that the fabrics were soft and comfortable to the touch and could wick moisture. The first item was a Christmas gift, a Polartec fleece headband for running outside in the dead of winter in Toronto. When I went for a run wearing it for the first time, a day or two later, I didn’t think much about how my ears and head were warm and dry, until I got home, took it off, and was amazed to see the beaded moisture on the outside surface. The second item was a wicking polyester t-shirt that I bought for triathlons (and only for triathlons–it was expensive enough for me at the time that I saved it for race days). I could pull it on over a wet swimsuit and get on my bike, without worrying that it’d end up soaked and clammy like all the cotton t-shirts I normally wore to train. When I starting spending time there in the late 90s, I joked that the tech boom in rainy Seattle was facilitated (if not driven) by the rise of Gore-Tex. Since then, I’ve been keeping a close eye on advances in textiles as they move out into the mainstream (for me, that means 100% synthetic workout clothes from REI and the Gap–no more cotton t-shirts, ever–plus a few items from Nau and Outlier, and also amazing microfibre dishtowels). So I predictably absolutely adored this piece in Aeon about how textiles are a technology that has been underappreciated throughout history. A day or so later, a friend commented on the post-apocalyptic clothing in Mad Max: Fury Road and elsewhere, and that sent me down a late night rabbithole.

Given a vaguely-specified Hollywood-style apocalypse, where we ignore how going back a hundred years in technology will make the Black Death (and its associated massive cultural change) look like a day in the office when everyone is at home with the flu, what might clothing look like, say, a decade or two afterwards? If everything is pushed back to the level of handbuilt tech, the biggest issue with clothing is that there won’t be much of a supply chain. No supply chain means that, at least in the short term, the local clothing stocks will be a major determinant of what people wear. Where I live (the northeast US), that means cheap and ubiquitous t-shirts patchworked into everything, for a start–making quilts out of a hundred thousand unneeded t-shirts. Notions (zippers, hooks, buttons etc.) will be cannibalized from worn-out clothes–even cheap zippers bring together out-of-reach precision metallurgy and polymers, and reliable YKK zippers will be sought and prized. Speaking of polymers: Patagonia and North Face and Gore-Tex outerwear will be prized heirlooms, the most valuable garments made of durable, functional and irreplaceable technical synthetics (especially needful in New England winters). No supply chains means no polymers, nor much by way of dyes (most of which are derived from petroleum), which means returning to fibres that can be grown (and grown locally, initially). Plants or animal products like wool, as well as leather (probably not black, though) and fur. This was nicely captured in Mad Max: Fury Road: the Vuvalini of Many Mothers, who gardened, wore handwoven-looking scarves and fabrics in colours consistent with vegetable dyes. No sweatshops on the other side of the world means that the urban hipster hobbies of knitting and sewing are suddenly survival skills, assuming that raw materials can be found (and disposable sewing kits from hotels become immensely valuable for the sharp, strong steel needles). The city of Lowell, just north of where I live, was built in the 1820s as a factory town to manufacture textiles. Many of the canals, some of the water wheels, and a roomful of looms have been preserved as a national historic park. While they could be converted back to water, the timescale of that seems long enough that other technologies might be rebuilt.

This is just off the top of my head–I wonder about needles, about spinning strong but fine threads, about how warm clothes allow mobility in the wintertime. But ultimately, it’s hard not to feel like the idea of a catastrophe as a short sharp shock is an artifact left over from the Cold War and the insanity of concepts like ‘full-scale nuclear war’ and ‘mutual assured destruction’ and ‘nuclear winter’. The catastrophes that loom over us now are all happening in slow-motion: anthropocentric climate change, planetary-scale pollution, peak oil, pandemics (or some combination of all of the above, as occurs in William Gibson’s The Peripheral and referred to, with grim humour, as the Jackpot), which will likely allow at least some evolution in what people wear as they play themselves out. One thing is for sure, though–there’ll be mismatched plastic buttons everywhere, since they need millions of years to decompose, and crafters will be finding stashes of those suckers until the sun goes out.

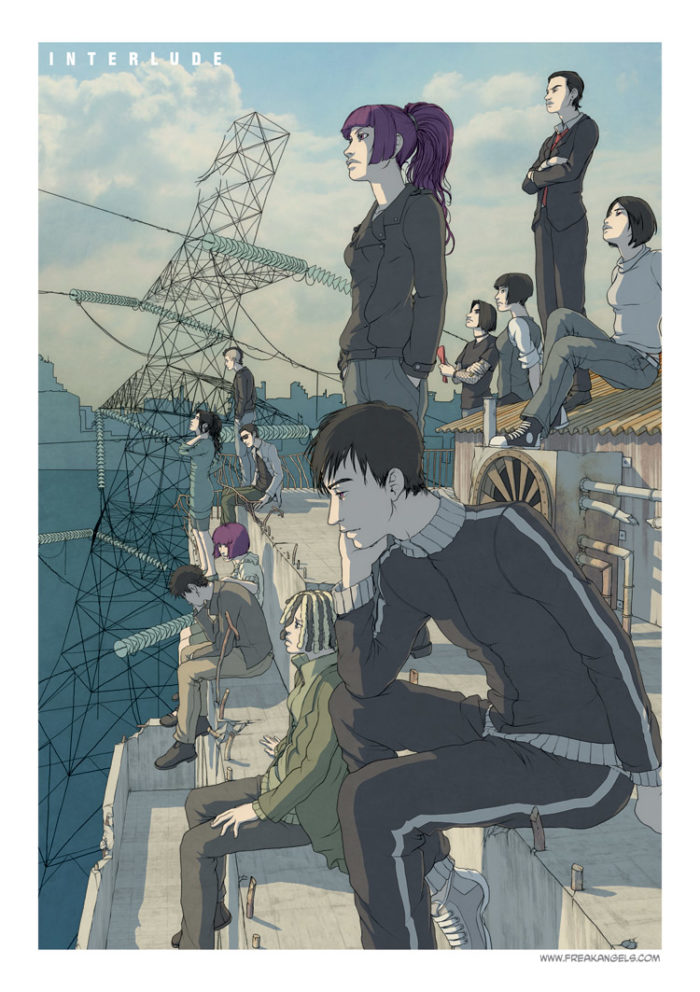

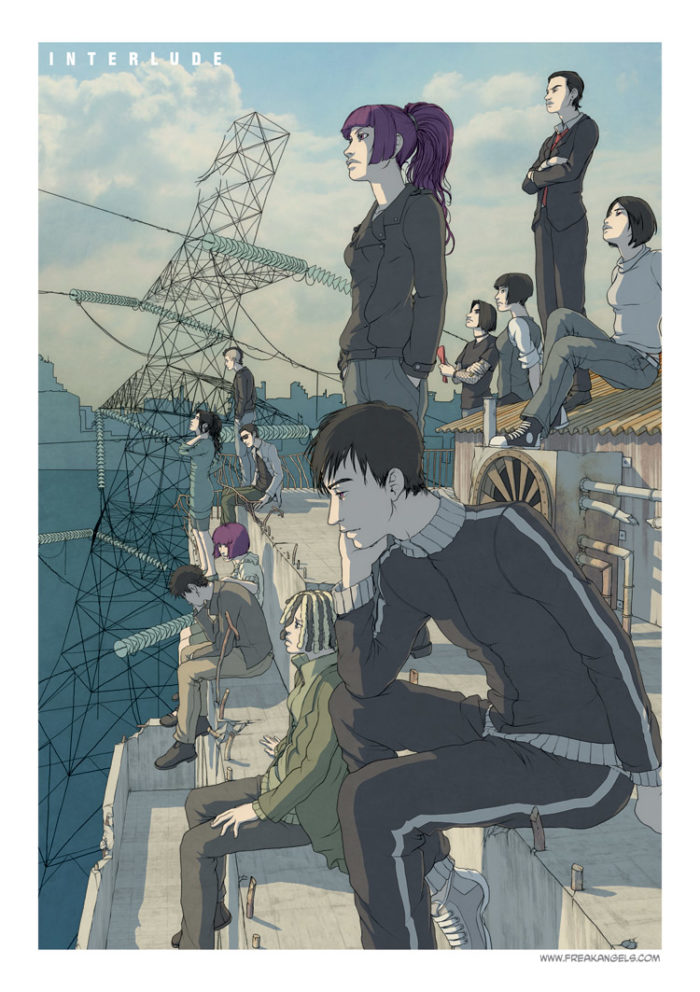

And finally, I feel as though Warren Ellis & Paul Duffield’s Freakangels might have been the original solarpunk text, without realising it and long before the term was coined. Think about it – it’s set in a flooded world, and follows the exploits of a small group of people struggling to build themselves a sustainable community without help (or interference) from any authority but themselves.